I arrived in Delhi late at night and having never spent time in India previously I was of course amazed by the apparent chaos of the place. For a very ordered and organised person, the sights, sounds and machine guns that greeted me at the airport were all a concern.

I took a Taxi to Lajpat Nagar Part 2 and the residence of Priya Ravish Mehra, a four story building in a middle class suburb to the southeast of Delhi. The residence is made for the hot climate at this time of year, with high ceilings and slate floors it provides some welcome respite from the humidity outside.

Living in the residency at this time are Vangelis, a Greek dancer and choreographer and Freda, a Swiss puppeteer. There is a creative energy in this place that is inspiring and they welcome me into their home openly.

I was aware, more than anything, that my time in Delhi was short, so the next day I set about organising as many meetings as possible to try to make the most of a short period. While I was awaiting responses I spent the first few days finding the lay of the land and getting to know Delhi a little better.

I visited the parliament building and explored the vibrant alleyways of Old Delhi. Old Delhi is an area of the city that grew under Mughal rule and as such Islamic influences can be felt everywhere, from the Mosques to the elaborate and slightly unexpected ornamentation of the Red Fort. This is still an incredibly vibrant part of the city, a bazaar tightly packed with goods from all corners of India. Here you can buy anything – spices, silk, food and hardware of all shapes and sizes. As a designer I could not help but imagine living in Delhi and being able to come to this neighbourhood for anything. There were men and women carrying reams of paper and stacks of large copper s-bends on their heads. There are no couriers here.

|

|

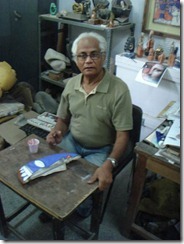

My first meeting was with Shyam Prisad, a contact that I had received from the very generous Sandra Bowkett. Shyam comes from a long line of potters, but he has taken up photography. I met with Shyam at his photography school, not far from the residence in Lajpat Nagar. I was interested in meeting with Shyam because his father is a very well known potter in Delhi – Giriraj Prasad. Shyam is a very generous guy, welcoming me into his studio and showing me through his work. We spoke at length about his father’s pottery and Shyam invited me to visit his father at his studio on the outskirts of Delhi.

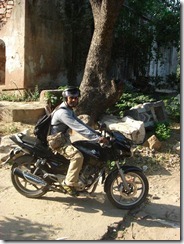

On the 13th of October I was up early and in an auto-rickshaw by 6am. Giriraj’s studio is a long way out, and if you get stuck in the morning traffic it is much longer. The ‘auto’ is a bumpy and noisy way to travel such a long distance, but I couldn’t find a taxi… After about an hour meandering our way out of Delhi the driver began to stop, asking people the way. In my experience, this is how you know that you are getting close.

We pulled into a suburb with dirt roads. The area is buzzing with the activity of the early morning – 6 neatly dressed kids on a cycle rickshaw headed to school, men having their morning shave on the street, dogs and cows rummaging through the rubbish and vendors of every kind selling breakfast in too many forms to mention. This place is lively in a way that a neatly primped, heavily landscaped Australian suburb could never be.

The driver continued to enquire after our block number until he eventually stoped the auto and gestured toward a small alleyway. At first I was not sure how this could possibly be the place, but then I saw Shyam standing in a doorway. He beckoned me inside, welcoming me with great generosity into his home.

Tea came first of course. A small cup of very sweet, very white tea. For someone who usually takes their tea ‘raw’ as they say in India (no milk, no sugar), this was a welcome treat. The novelty of having a tall white guy in the house soon became apparent as Shyam’s young daughter ran in and out of the room where I was sitting giggling. After we finished our tea we walked back down stairs where Shyam said goodbye to his daughter and wife as they made their way to the local school.

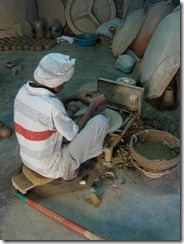

By this time Giriraj had arrived and it was time for me to meet the great potter. Shyam and Giriraj showed me through the studio, located across the alley from Shyam’s family home. On first consideration it is a fairly rundown, old brick building. There were bays piled high with terracotta dust and pots everywhere. They showed me through to the area where the work takes place; Shyam was directing me, while translating his father’s Hindi. In the main room there were two people working. A man

was sitting on a small cushion on the floor, hunched over a wheel. He was throwing small pots with great accuracy and speed, taking no more than one minute to throw each one. As he finishes each piece they were lined up on the floor where a young woman was sitting, adding surface detail. She was using a knife to cut an intricate pattern of wholes into the surface, designed to let the light of a tea-light glow through.

I began to ask the typical questions of a foreigner. “Wouldn’t they be more comfortable working in a chair” and “Don’t they get saw sitting on the floor all day”. Shyam explained to me that they are able work in anyway they like, but this is their choice. At any one time Giriraj has from 2 to 5 people working for him, from unskilled labourers who might move terracotta dust or un-pack the kiln to skilled labourers who throw and decorate. An unskilled labourer will be paid around $5000 Rupees per month and a skilled labourer around $10000 Rupees per month. In India the minimum daily rate of payment in 320 Rupees per day, so in the scheme of things an unskilled labourer in Giriraj’s studio is paid quite poorly, while a skilled labourer is paid well.

As I ask these questions about payment and working conditions I begin to worry about the livelihood of these people and wonder why they cannot be paid more for their work. These questions are answered a few days later at the potter’s colony.

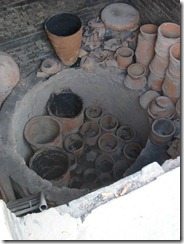

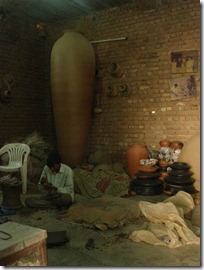

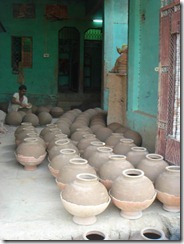

Giriraj Prasad only works in Terracotta and is renowned for making very large pots. Giriraj is a man of around 5 feet, but he makes pots that are up to 12 feet tall. These large objects have a beautiful symmetry and are incredibly refined considering their size and the coil construction that is used to build them. These pots are fired in a wood-fired kiln on the premises, where they use either a pure firing to maintain the redness of terracotta, or a smoke firing to render the pottery with a matt black finish. The pots are then either left rough or polished with a smooth stone to give a smooth finish to the terracotta.

The shape and materiality of this work is influenced by Giriraj’s Rajasthani heritage, from what I understand, Giriraj moved to Delhi as an economic refugee along with many others in the 1970s when it became too difficult to survive making pottery in Rajasthan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A five-minute walk from the residence in Lajpat Nagar there are a group of artist’s studios called ‘Gari Studios’. After several unsuccessful attempts to find the studios I eventually located the Gari neighbourhood and then the studios that sit at the entrance to this section of Delhi.

The entry to the studios is a stone archway in a fairly non-descript wall, but on the other side is an internal courtyard that is thriving with plant-life in a way that most areas of Delhi do not. Crisscrossing pathways cut up areas of lawn, and within each pocket of lawn is a beautifully maintained garden bed with trees and small shrubs. Around the perimeter of the courtyard is a neatly trimmed hedge, facing onto a pathway that provides the major pedestrian walkway for the garden. Surrounding all of this is a ring of buildings – artist’s studios and offices with marble sculpture, half finished canvases and pottery pouring out onto the outer pedestrian ring.

As I walked around I notice that many artists were hard at work, while many of the vast workshop spaces were empty. Walking the perimeter pathway I was beckoned into one of the smaller studios by an older Indian man.

Amitava Bhowmick is one of the residents here and he sits me down and offers me a cup of tea. As we began to chat I asked about the Gari Studios and how such a beautiful space could be provided for artists in a city that has so much poverty. He explained that artists are given studios at Gari, they pay rent, but the amount is very little. He goes on to say that this system is something that harks back to India’s Socialist past and its belief in the importance of art.

Amitava began to tell me about his work. He was a marble sculptor until RSI in his hand stopped him from sculpting. His studio is overflowing with large marble figures – evidence of his many years as a sculptor. Now Amitava is a drawer and a painter, but as much as anything he is a philosopher, speaking with me at length about his ideas of the world. In the days that followed I visited Amitava almost everyday for a dose of his philosophical rhetoric and a sweet cup of tea.

Eventually I asked Amitava if he knew of any marble sculptors still working at Gari. I had an idea for some small table tops that I was hoping to have made, and having seen the abundant use of marble in India, I thought that this would be the perfect medium. He arranged for me to meet with Jabid, a young sculptor who often worked for him and we began to discuss what I wanted to have made. Firstly I arrived with technical drawings, and while these helped a little it was soon clear that Jabid was not used to reading technical drawings. I began to sketch the form that I was looking for and with some translation from Amitava we eventually came to an agreement. I was

not completely sure that Jabid knew what I was asking for, but Amitava suggested that I come to the studio to work with him, so to ensure that the outcome was correct.

Once an understanding had been reached it was time to discuss the price. This was a major source of concern for me, as I was worried that Jabid would not ask enough for his time. I was pleasantly surprised when Jabid quoted me 3000 Rupee per table top (Approximately $60, a price that I might expect to pay for the same component in Australia).

Jabid spent the next day or so sourcing pieces of white, black and pink marble – one for each table. After all of the pieces had been found I marked the cut lines on each piece and Jabid began. After a few days of grinding and polishing the table tops were complete. The end result was beautifully imperfect; the parts were to my specifications, but contained lovely imperfections that an only come with making something by hand; details that cannot be specified.

|

|

On the 14th of October I accompanied Kevin Murray to the Jindal Global Law School for a conference that was organised to open discussion around the legal and ethical dilemmas that surround craft in India. The law school sits in a compound approximately an hour from central Delhi. Housed in a gated facility, it is necessary to pass a security check before entering the university grounds. Once on the grounds the law school protrudes from its otherwise undeveloped surrounds – a large box-like building that resembles a multilevel car park from a distance, but on closer inspection there has been a degree of consideration given to the design of this building, and while it is not to my taste, it provides an interesting backdrop to the conference.

The conference opens up dialogue around the fading crafts of India, those that have existed for centuries, but are beginning to be overshadowed by technology. We discuss the dilemmas that this situation brings about for many families throughout India who rely on these crafts for a livelihood and possible solutions to this problem.

One popular and seemingly logical solution is to bring in business from overseas to make use of these traditional skills, but this opens up another ethical dilemma all together – worker exploitation by the developed world. These ideas are then analysed – It seems that many ethical designers and producers are reluctant to come to a place like India for production (at any scale), as the question of ethics in this situation is too complex to tackle. As the discussion continues we begin to realise that because of the caste system there is a great deal of domestic labour exploitation. Crafts people in India are almost without exception from a low caste – as such their work is not valued and their rate of pay is much lower than that of a person working an office job for example. There is an argument that the crafts are held in higher regard in the developed world and as such there is an opportunity for these crafts people to be paid well as a result of working with foreign producers. In essence these crafts people are often exploited by their own population, but an ethically minded foreign producer could bring larger financial rewards, resulting in more sustainable business models.

I have always been one to shy away from making in countries like India and China, as there is such a complex web of contributing factors surrounding the question of ethics that it has always been easier to just leave it to one side. This new point of view (specific to India) has made me reconsider my initial preconception and begin to understand some of the complexities of the situation.

Of course there are many other areas that come under the microscope when discussing labour related ethics. High on my list of priorities are the working conditions that one might expect to find in India. Through continued discussion I begin to learn more about the work structure of the majority of producers in India. Because of a

deeply rooted historical model, the vast majority of production in India is a result of crafts practices, rather than large factories. These craft practices are often family run and operated – in many cases the entire (often small) workforce are family. As a result these small craft practices are very small and self-governing; they decide their working hours, they set up their own facilities and they negotiate their own pricing. For me, this is an ethical model to engage with, as I can be sure that this family of crafts people are not being forced to work long hours against their will, or in conditions that they are not happy with. Ultimately (with some financial injection) they have the power to shape their own work environment and after some long consideration, this is a model that I would be happy to work as a part of.

The conversation continues onto an interesting area of discussion – labelling of saleable pieces and the transparency that labelling can provide. We discuss the ways in which labelling can clearly communicate the ethical considerations of the producer – including fair labour, sustainable material use, place of production, individuals involved in all stages of production etc. This is an area to which I have given some thought in the past, and one that interests me greatly. I am very keen to be transparent in my work, giving the potential purchaser the complete story of any design piece from conception to production, including information about the conceptual underpinning of the project, as well as the ethical criteria that govern its production. We discuss the amount of information that needs to be listed in order to give a truly detailed account of all of these elements and it becomes evident that the standard archetypes for labelling will not allow enough physical space for this necessary information.

From this discussion I have made the decision to alter aspects of my website so that I am able to list more information on each of my pieces. As an ethical consumer I know that I am always looking for straight and factual information on the things that I purchase, so that I can make ethical decisions. I refuse to rely on the uncertain judgement of accrediting bodies who slap their label on a product and expect us to take their word it. I want to know the simple facts – place of production, materials used, the situation under which the materials were sourced, the details of the labour that was used to produce the piece etc. As my range grows I want to make all of these elements completely clear on my website, as a form of transparent labelling, that is not actually attached to the work, but is easily and freely available to those who are looking to know more.

On the 19th of October I had agreed to meet with Sandra Bowkett, so that she could take me to visit a potter’s colony that she has had a lot to do with in the west of Delhi. I met Sandra at the closest metro station and we jumped in an auto-rickshaw – the only way for two foreigners to make their way into the depths of these meandering suburbs.

After some negotiation with the driver we left the metro, headed down a choked river that smelt more of excrement than water. We made our way through the small suburbs of an area of Delhi that few visitors would get to see. This is not an area that tourists would generally be interested in; there are no markets or temples here, just ordinary Delhi residents going about their daily routines.

Sandra has been coming to this colony for ten years, but this area is so dense and confusing that she still does not know how to find the colony without the help of a local auto driver. It is only when we are within a few blocks that Sandra begins to spot a few familiar landmarks and finds her bearings.

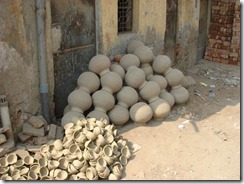

Once you are in the vicinity of the potter’s colony it would be difficult to miss. Pots of all shapes and sizes line the streets, piled up high against the buildings and hundreds of outdoor kilns that dot the suburb. The roads are unpaved and as the pots flow out onto the street it becomes difficult to delineate public and private space. My first impression is that this must be a truly communal place where people work and live side by side with no need to lock up stock or delineate arbitrary boarders of ownership. As we walk down the street Sandra is greeted by members of the community who have grown to look forward to her presence. People sit on the ground in the shade throwing ‘Tali’ – small dishes that are used to light candles at Divali (the impending celebration, often dubbed as the ‘Indian Christmas’). Another man sits in a beautiful old brick building surrounded by an army of ‘Mudka’ (water jugs), beating them into shape with a special tool that looks a lot like a thick table-tennis bat.

Further down the street we come to the house of Minori, a man who Sandra has spent a lot of time with, both in India and Australia. Minori and his family are over-joyed at Sandra’s arrival – Sandra has been a great friend to them and from what I can tell she also represents opportunity for many of the potters living in this community (Sandra has organised exchanges, bringing potters including Minori to Australia to work with Australian artists and to sell their work in Australian galleries).

We sit down outside Minori’s house under an awning where they are working. We watch Minori’s two sons throwing Tali in tandem. One son throws these small dishes, while the other quickly cuts the dish off and places it on a plywood board. It takes them no more that 10 seconds to make each one, and their efficiency is startling. Sandra begins to speak with Minori about the remuneration that they receive for items like the Tali. From memory they receive 3 Rupee per Tali (about 6 Australian cents). Minori’s son has also spent 5 hours that morning throwing around 100 terracotta planters (plant pots approximately 300mm in diameter and 400mm high), for which the family will receive around 15 Rupee each (approximately 30 Australian cents).

The entire family works here – the wives make the clay while the husbands throw the objects, collect timber and fire the work in large wood-fired kilns. There is an incredible amount of intuitive knowledge that goes along with this process, from the mix of water and clay to create the correct consistency, to the identification of a certain colour red that the fire reaches in the kiln when it is at the perfect temperature for firing. This is all low-tech and completed in a manner that is second nature to these people. There are no production notes or gauges here, nothing is designed to ensure consistency, but they do this all day, everyday and the routine of these actions ensures an incredible level of consistency.

At the end of the line the family’s wares are all purchased by local buyers and sold on the domestic market, but the family explain that hand made items, like these pieces made by the potters, are not respected by the average Indian. People in India are for the most part obsessed with modernity and long for objects that are machine made. As a result these potters cannot ask a high price for their wares. To add to the dire nature of this situation, potters are a low caste in India and as such their labour is not respected, and the amount paid for pottery reflects this attitude.

|

|

|

|

On the 21st of October I see Minori again at the Sangam Round Table. The round table is a conference organised by Kevin Murray to open up more discussions around the fading crafts of India, but this time some of India’s most important supporters of craft are invited, along with designers and crafts people from India and Australia.

Kevin continues discussions on the use of Indian craft by Australian designers and interestingly discussion on labelling systems for crafted products continues. We talk about the kinds of details that could be listed on the labelling of an object in order to fully inform the consumer of the elements of production – labour, the story of the maker, location of production, situation of production, materiality, transport etc. The list is quite long and most agree that such a large amount of information cannot be listed on a physical label. Discussion begins about other ways in which this information might be made publically available. The internet is an obvious answer, but perhaps this is still an exclusive mode of communication, especially in a country like India where most would not have access to the internet. In saying this, I think that a web listing is the only logical way to make such a large amount of information available, and even if it is not available to all, it will be available to many.

As we go around the room we learn about the work of individuals. Most seem to be designers who have used Indian crafts people to produce their wares and most seem to take a very business-like attitude toward these relationships. They discuss problems with consistency, getting crafts people to venture outside their comfort zone and intellectual property. I am keen to discuss intellectual property and ask the group their experience with asking local crafts people to sign non-disclosure agreements in order to assure that an idea will not be copied. The unanimous opinion is that Indian crafts people do not sign contracts and the very mention of a contract would be seen as a breach of trust. Things here are done on an honour system. In saying that, they all agreed that in most cases a crafts person would make your work for other people if there were the opportunity for financial gain, and perhaps would not understand why this is not desirable. These experienced designers spoke about strategies for avoiding this including – having different components made by different crafts people and assembled in Australia, so that the pieces can never be assembled and sold in India.

The discussion continued on strategies for helping preserve Indian craft. Most ideas centred on evolution; the evolution of these crafts, in order to make them relevant to a wider market. Most Australian designers working in India are attempting to have local crafts people evolve their craft in one way or another, asking them to do one thing or another differently, so to make the result more relevant to a particular market at home. All involved in this conversation have had trouble with asking crafts people to try new things. Mostly these designers come against resistance when suggesting a new mode of production, being told that it is not possible. Of course in many cases it is possible, but the crafts person has been practising in a traditional way for such a long period that the methods of production are deeply entrenched. My question is – if the craft is being forced to change, is it really being preserved? Surely some of the beauty of these crafts are caught up in the traditions of specific techniques, colour usage, stylistic archetypes etc. that have been passed down from generation to generation. If these elements are diluted through foreign design vision, is the essence of that craft lost?

One interesting subject of conversation was the transparency of supply chain. Put simply, Kevin was interested to know whether it would be beneficial for crafts people to know the intricacies of the supply chain from India to Australia, through wholesalers, retailers and finally the end price in a store in Australia. Kevin has heard many accounts where relationships have fallen-out between designers and a makers when the maker learns the final sale price for a piece that they are making. It is Kevin’s idea that perhaps an open and honest conveyance of the full extent of this supply chain and the mark-ups that occur along the way would prevent this. This idea was met with resounding resistance. Most people said that there was no reason for the maker to know this information and that, in many cases, the maker would not understand the

steps that are taken along the way, and the reasons for these necessary mark-ups. It was the opinion of most that it would be too difficult to explain this situation in a way that the maker could understand without a complete knowledge of this area of business. This was interesting to witness, and although I have no strong opinion on this one way or the other, it is interesting to note the presumed educational divide between designer and maker.

One point that came up time and time again was the idea of paying crafts people “fair” wages. My largest concern is that “fair” is such a subjective idea. Can we place a dollar amount on fair? I have learned during my time in India that the base wage for an Indian worker is 320 Rupees (approximately $6.50) for an 8-hour day. Is this a fair amount considering the comparatively high price that Indian craft products sell for in Australia? Surely designers should be coming to India to source skilful, historically significant craft practice, and not cheap prices. In my opinion a designer should be paying very close to what they would expect to pay in Australia, ensuring that the crafts person is being paid what the designer would want to be paid for the same labour. How is it possible to justify anything else?

In all the conference was very interesting, there were many interesting topics of conversation and it was beneficial to learn about the experiences of others working with crafts people in India. All of this has given me a lot to consider when it comes to the ethics of production in India, but I feel that whatever my decision, it will now be a more informed one.

Two and a half weeks is not a great deal of time to spend in complex city like Delhi, but during this period I feel that I have begun to understand the collaborative opportunities that might exist between a designer such as myself and traditional crafts people like the potters of West Delhi. At this point I am more open to the possibility of collaborative projects than I was previously. At the very least my concerns about the ethics of working with crafts people in India have been lessened, but in many cases these concerns have been replaced with apprehension about the level of commitment required in order to ensure polished outcomes. I am glad to have made connections with members of the potter’s colony and Giriraj Prasad, and will attempt to explore projects that might be relevant to their skill-set, but this type of collaboration would not be entered into lightly. In order to maintain a level of consistency in the work produced it would be necessary for me to visit Delhi regularly, monitoring the work being produced. I am not sure that my current trajectory will allow me the time for this level of commitment. Similarly I am not sure that the manufacturing companies with whom I am currently working would be willing to devote the amount of time necessary to ensure positive outcomes.

Ultimately I am interested in engaging with these crafts people for the positive influence that a growth in productivity might have on their community. To this end I will continue to consider collaborative commercial projects that might enable these potters to command greater remuneration for their labour.

One solid outcome of my two and a half weeks in Delhi are a series of table tops made from Indian marble. These table tops are to be used in a series of tables called ‘Christopher – Made in India’. ‘Christopher’ is a table that was designed as a biographical interpretation of a man who has had a very strong personal influence on my life. The initial Christopher table (yet to be prototyped) will be an exploration of Christopher’s character as he was. The series of ‘Christopher – Made in India’ tables are an exploration of Christopher’s character as it could have been. Christopher’s parents moved from India to Australia and Christopher was the first of his siblings to be born in Australia. This series of tables aims to explore the way in which Christopher’s character may have evolved if he had been born and raised in India, as easily could have been the case. In the completion of this series of objects I plan to go back to India, making use of local crafts people to construct the remaining components.

Trent Jansen was the inaugural designer in resident at New Delhi Residency as part of the Australia India Design Platform. His website is http://trentjansen.com.