Alejandra Gomez, a student of RMIT Sangam Studio, travels to Pekalongan in Indonesia to experience the soul of batik. Finding similarity with the practical lives of her Colombian family, Alejandra immerses herself in the batik world. Along the way she learns an important lesson about coconut.

The Profound Effect of Batik from Alejandra Gómez on Vimeo.

Introduction

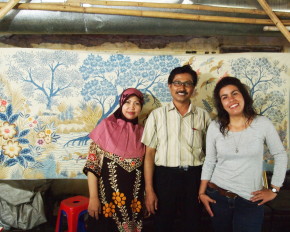

Sangam studio showed me a very meaningful way of living through batik. It gave me the opportunity to meet new friends due to our common interests in batik culture and practices.

My proposal project is called “The Profound Effect of batik”, a documentary film that shows the values of batik as a human made products. It offers the viewer an opportunity to understand and learn that “design always has a history, it belongs to a tradition and it is part of a system”.

Batik’s values are the principles that the industrialised and modern western societies are lacking due to the unvalued and very disposable material world in which they are part of it. This documentary film intends to express what I have learnt during my stay in Indonesia, a very short travel but one very rich in new knowledge.

Through this documentary film I would like to highlight the work and lives of the batik artisans by appreciating, supporting, respecting, recognising and communicating their values. The future of batik will always be kept as a tradition, because Javanese people love and respect their culture.

Batik Friends

Mutahdin is the third generation in his family that practices batik as a profession. Batik has been passed from his grandfather to his father, then from his father to him and he is hoping to do the same with his two young sons. Mutahdin and Heny Agustina Lusianti, his wife, own together a micro batik company with 10 workers that come five days a week to his workshop and other 25 batik makers that work from their homes. He always provides and delivers the materials to these workers. He and his wife as well teach batik at the Unikal University at Pekalongan. The batik that they produce is for everyday wear rather than a collection. Mutahdin is thinking to develop a low technology system or product that purifies the contaminated water used in the batik production.

Sapuan is the best batik artisan in Pekalongan and one of the best ones in Java. He is very well known internationally and sells his batik to collectors and museums. His work is very intricate and time consuming. Just one piece of batik takes one or two years to be finished. Sapuan works with the help five other workers. His workshop was very clean, contrary to other batik workshops that I visited in Pekalongan and Bali.

Zahir Widadi was the person that helped me to meet all the artisans and other batik contacts in Pekalongan. He is very much the face and representative of batik in Pekalongan. I was very fortune to have him as company to tour and tutor me around. At the moment, he is building a very well designed batik workshop at his house. It is only for making natural batiks, which means that the workshop needs extra space for the preparation and storage of the natural dyes. He sees the future of batik only using natural products. He is encouraging the batik students from UNIKAL University to learn those techniques, even though these are not very easy and quite time consuming.

Thursday is delivery day

Every Thursday is the delivery batik day in Pekalongan. The batiks cover the back and part of the front of the motorcycle. There is no need to use a bigger form of transportation because batik production is small in quantities. One batik takes one week to be finished. In one week, a batik artisan can produce around 400 batiks.

Tyranny of Distance

Starting this studio, I booked a flight to Indonesia very early with little expectation of what the travel would bring. From my experience with Facebook, I realised that if a designer wants to produce a project or a product with Indonesian artisans it is very much compulsory to travel to Indonesia to find the right contacts and samples. Communicating by emails or Facebook doesn’t guarantee that you will have a finished product in Indonesia to be sent to Australia later on.

Indonesia is a very traditional country, mostly driven by the Muslim and Hindu religion which takes up a lot of their time. During my stay I had the opportunity to experience the celebration of iron materials, when everyone washes and decorates (with flowers and fruits) their products made of iron, such as cars, motorcycles, money, houses and tools. Then people went to the temple with some of those decorated products and prayed for them all the morning or night.

In some parts of Indonesia such as Ubud, Semarang and Pekalongan, the Internet was very, very, very slow… in comparison to Australian Internet. So this condition makes even more difficult to maintain a business remotely. In general, the artisans of Indonesia don’t complete their school education. They are not so aware of business matters and selling to international markets is not in their minds. Their houses are their workshops. While making crafts is part of their identity as an Indonesian, they are not experts on selling their products to international markets.

Living with a Javanese batik family for five days was a most enriching experience. I also had the opportunity to talk and do some batik work with the best batik representative artisans of Pekalongan and batik students of UNIKAL University. These conversations helped me understand that batik in Java is a religion. It’s a way of life.

The coconut day

… In the morning, my new mom invited me to go with her to the traditional market to buy the breakfast and the ingredients for today’s lunch. She bought some traditional food for the family and the batik workers as well (every morning she does this dairy shopping, just before 8 am). While she was doing the shopping I walked around the market and was craving to eat a coconut.

For some reason the woman that was selling the coconuts looked at me with a funny face trying to say… ‘Why do you want to buy a coconut???’… We didn’t have any kind of Indonesian or English communication, just communication with gestures and simple signs with the hands… continuing, I couldn’t understand what the woman was trying to explain to me… All I wanted to do was to eat a coconut… I was asking to myself: ‘Why can’t I eat that coconut???’…. Neither of us understood each other and I continued explaining to the same woman how to cut the piece of coconut I wanted to eat… after some time, the woman at the end followed my idea and gave me the coconut. I took the coconut and continuing walking around the market…

Seconds later, I could feel that everyone in the market was looking at me with funny and curious faces again… I continued on with my delicious coconut, but not understanding what was happening. My new mom and I met again, and again she look to me with the same funny face ‘Why I was eating the coconut like that…???’ All what I thought was… ‘Why can’t I eat the coconut…???’

It turns out that in Pekalongan, people don’t eat fresh coconut, they always cook it. So, for everyone it was very funny to see a stranger eating coconut in that way.

Tyranny of Communication

One of the decisions I made in Pekalongan was not to have a translator, and instead to see how I would manage and survive my stay with no English communication at all. The only person that spoke very good English was Zahir, but I spent most of my time with Muhtadin, his family and the UNIKAL’s students.

This condition made the research even more interesting and exhausting, but very well worth it. I don’t regret not having a translator because I could discover new methods of communication. The Indonesian-English dictionary that I always carried with me was used by every Indonesian that I met. People were very curious about my visit and they always wanted to know something about me, my country or my profession. I always encouraged people to use my dictionary if they didn’t know how to explain or describe something to me. Crossing communication was very much based on sentences with just three or five words. It was limited, but the whole experience was amazing.

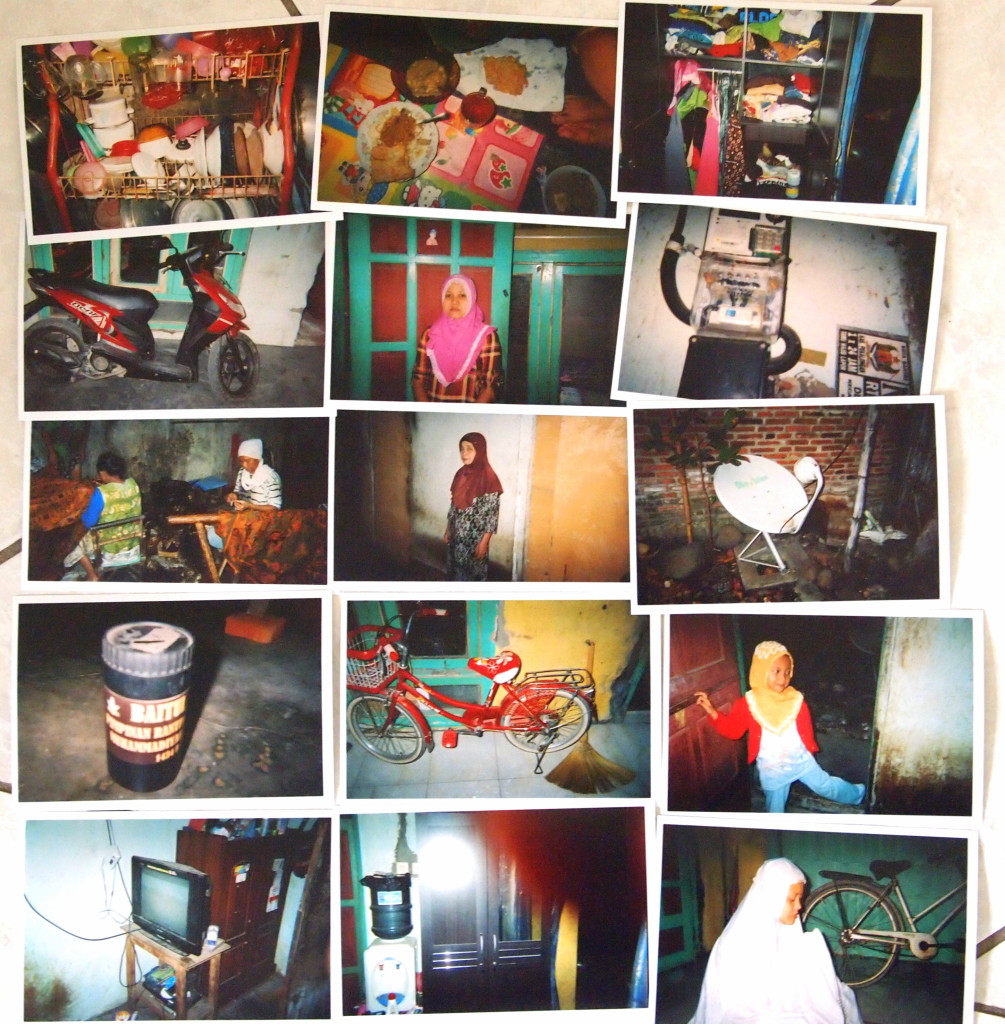

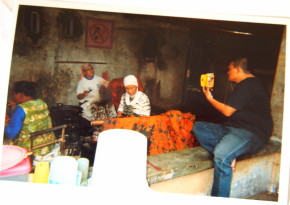

I sought responses to the question ‘What does batik mean to artisans?’ I brought from Australia two disposable cameras with the objective to communicate with pictures as a method of research.

It took me almost 30 minutes to explain to Muhtadin and his wife my plan to lend cameras to two batik artisans who would respond to my question though pictures. The artisans understood Muhtadin well and the following day they brought the cameras with the all the film finished.

In Australia I developed the film, and for my surprise the pictures were very beautiful. These pictures didn’t just respond my question but as well gave me artistic answers. Looking at the pictures, the message that I can understand as a response it is that batik for the artisans means their lives. The pictures show their families, their homes, their transportations, their food and their dreams.

Making the Old, New

In a first instance, as an Industrial Designer I don’t find that batik processes need to change. This is what makes it so authentic and romantic (despite all the environmental issues, but at this point I only want to concentrate in the positive aspects for this project).

From my personal perspective, I understand the value they gave handmade objects. I grew up looking my grandmother making dresses, skirts and blouses. She educated and fed all my family with her hands and eyes, sewing almost every night until midnight. This job started just as a hobby, but higher education was not available for my grandmother at that time. She learnt to sew from my great-great grandmother and some classes from her primary school. After a few years, my grandmother got married and started to make a family, but one day my grandfather had an accident at the job and died unfortunately. My grandmother became a widowed very young with four children (my youngest aunt was months old and my oldest uncle was 8 years old).

So, I believe that my grandmother’s story is very similar to many women batik artisans’ stories. In the past, women didn’t have many options to become professionals. Getting formally educated in a university was a titanic dream. But learning a craft skill was a very good way of making a life and sustaining a family tradition.

In terms of design, I found that batik needs to simplify the designs and patterns for foreigners. Making patterns well balanced and modernised, minimising the batik design and production process is more important (but not unethical) if the goal is to sell in international markets to compete with industrialized mass production fabrics companies.