In February 2006 I flew to India from Australia with camera man Mike Crowhurst, production manager Shalu Sood and my father Ken Butler to embark on a one month community art / design project that I had dreamt up the year before. My task was to see if it was possible to generate employment for Indian artists and to keep the cultural traditions of their work alive in the face of India’s rapid modernisation. Hopefully others can learn from my experience and be inspired to do similar projects.

In February 2006 I flew to India from Australia with camera man Mike Crowhurst, production manager Shalu Sood and my father Ken Butler to embark on a one month community art / design project that I had dreamt up the year before. My task was to see if it was possible to generate employment for Indian artists and to keep the cultural traditions of their work alive in the face of India’s rapid modernisation. Hopefully others can learn from my experience and be inspired to do similar projects.

We were hosted by Samparc children’s village in the rural mountains two hours East of Mumbai. Samparc is an organisation that supports children without families by housing them in a village community instead of an institutional orphanage. We set up a temporary art studio in the village hall and invited artists each day to work with us.

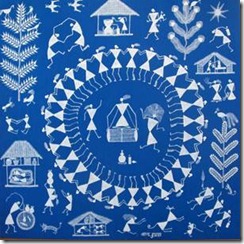

We invited a team of unemployed sign writers who hand painted beautiful Sanskrit lettering but were now unable to compete with the advance of vinyl cut lettering. We invited the last of the Bollywood artists who hand painted Bollywood posters, mainly now for tourists because digital photography and digital printing had made the artist’s work obsolete. We had two men from the Warli tribe spend several days on a bus to join us and paint scenes of traditional Warli life using their distinctive stick figure technique. We also invited young local women to paint traditional Rangoli patterns in vivid swirls of pastel colours and Mehendi (henna tattoo) patterns that are culturally used for wedding ceremonies. Several days were also spent conducting art workshops with local primary school children and students from the Mumbai art college.

We invited a team of unemployed sign writers who hand painted beautiful Sanskrit lettering but were now unable to compete with the advance of vinyl cut lettering. We invited the last of the Bollywood artists who hand painted Bollywood posters, mainly now for tourists because digital photography and digital printing had made the artist’s work obsolete. We had two men from the Warli tribe spend several days on a bus to join us and paint scenes of traditional Warli life using their distinctive stick figure technique. We also invited young local women to paint traditional Rangoli patterns in vivid swirls of pastel colours and Mehendi (henna tattoo) patterns that are culturally used for wedding ceremonies. Several days were also spent conducting art workshops with local primary school children and students from the Mumbai art college.

Our task was also to make a documentary about the project and the artists, take quality photographs and generally offer a creative exchange. I was also running my Melbourne based design practice by remote control using intermittent internet connection and given we had a one month window to complete this experiment in an unfamiliar country and culture my main focus was to keep smiling and be mindful of the pressures.

Our task was also to make a documentary about the project and the artists, take quality photographs and generally offer a creative exchange. I was also running my Melbourne based design practice by remote control using intermittent internet connection and given we had a one month window to complete this experiment in an unfamiliar country and culture my main focus was to keep smiling and be mindful of the pressures.

I went into this project with enthusiasm, naivety and a curiosity for the unknown. I knew that whatever happened, good or bad, the project would not be boring. For example the first time a westerner, such as myself, takes a taxi from Mumbai Airport to the city is a valuable lesson in respect for humanity. The road seemed like the aftermath of an explosion with rubble everywhere and as the dust settled the cars had taken over before humans had a chance to get back to their feet. There was no bomb, the road is like this all of the time. Families were living, sleeping and cooking within the rubble, dust and traffic. On a green light the cars, including ours, jostled like dodgem cars for a few seconds before halting again in the gridlock, having moved only a few meters. Our eyes and jaws were wide open in amazement. Having now returned to India a second time and also worked in other countries such as Cambodia, I am less sensitive to such experiences, but will always value the memory of this first Mumbai taxi ride and the impact it had on me.

|

|

Our first challenge, beyond the traffic, was to purchase the plywood, paints, brushes and groundsheets. One anecdote among many is it took about 3 hours of research and negotiation in a Mumbai paint shop to determine and have mixed the correct traditional pastel colours for the Rangoli artists. After making it clear over this time that we required water based acrylic paint it turned out we got dangerously smelly toxic enamel paint, not suitable for school children to use. The next morning I had to rush to a busy rural paint shop and use hand signals and face expressions to have the correct paints mixed before the town’s power supply cut out at 9.30am everyday. By the time I arrived late to our temporary art studio there were 30-40 artists, college students and primary school children waiting for me. I took some deep breaths and the Zaishu India project began.

The biggest challenge for anyone running a project in an unfamiliar country and culture is the pressure they place on themselves to get the job done. It is important to be mindful that some things won’t go to plan and are out of your control. This helplessness and frustration can easily manifest into unnecessary stress and negative thoughts that maybe you are not up to the task and don’t have the right aptitude or skill level to obtain the outcomes that are required. This is certainly what I felt every day. I questioned my ability to lead the experimental project, be a ‘people person’ in a social environment when I had work to do, negotiate with the artists and Samparc Village to make sure they were happy, collaborate with Mike on the documentary and find the energy required to absorb and process my new surroundings. I was also funding the project with AUD$18,000 of Zaishu’s money so I didn’t want to blow out costs, being mindful we should have at least $18,000 worth of sale able work at the end so we could at least break even.

As the weeks progressed a diverse collection of artwork was taking shape and we fell into a positive and productive rhythm. We got to know the artists and Samparc staff who were also eagerly painting away as it seems everyone in India has a creative side. The village was in a beautiful rural valley and the children were inquisitive and happy to have us there.

|

|

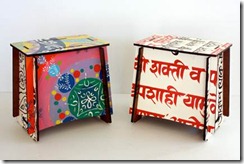

The artwork was painted onto large plywood panels to be shipped back to Australia and made into a furniture product called a Zaishu. A Zaishu is a flat pack design I created that consists of five laser cut pieces of plywood that easily slot together to create a rigid structure to be used as either a seat or table. This product can be posted to an online customer anywhere in the world inside a post pack envelope within 10 days and is certified with a Good Environmental Choice Australia certificate (GECA). Some of our customers include the Green Building Council, Westfield, Loreal Paris, Mini BMW and ski resorts in Sweden and Japan. The name Zaishu comes from the Japanese word Zaisu, a small seat used in traditional Japanese houses.

Over the course of six years, since 2004, the Zaishu project, operated by myself and fellow designer Helen Punton, worked in 22 countries with over 1,000 different artists and staged 105 exhibitions. At one point we had an exhibition opening some place in the world every three weeks. The first Zaishu project documented the work of Melbourne’s stencil graffiti artists by hosting an art workshop in a Melbourne lane way and an installation at ACCA (Australian Centre for Contemporary Art). Other projects saw us working with the St Vincent de Paul Youth Project, Odyssey House Drug Rehabilitation Art Therapy Unit, Tattoo artists in Berlin, street children in Buenos Aires, tribal artists in Fiji and graphic designers in Amsterdam, just to name a few. All of these projects were self funded and profits from sales supported the communities we worked with. The commercial arm of Zaishu that mass produced screen printed Zaishus in our own factory and distributed them worldwide provided the financial support to run the social community projects. We have now closed the factory and ‘wrapped up’ the Zaishu project to give ourselves time to work in some new directions. Sadly this means that there are no longer any more Zaishu seat / tables available. The Zaishu website can be found at www.zaishu.com.

The India project was one of Zaishu’s first international workshops and was a natural progression for us to record the visual information of a culture in line with Zaishu’s four word ethos of ‘Participation, Creativity, Sustainability (social / environmental) and Evolution’. As long as what we did fitted this ethos, we did it and rarely said no to any suggestions or collaborations.

It would have been impossible to run the Zaishu India project without local knowledge helping us on the ground in India. For this reason we teamed up with production manager Shalu Sood from ilink India who specializes in assisting western companies in India. Shalu helped to organize the artists, introduced us to Samparc Children’s Village and provided general support and advice for the project. Shalu’s parents were also very hospitable and helpful to us.

One unforeseen problem that required negotiation was to communicate with the artists and Samparc village that we were not rich westerners speculating to make money by exploiting their talents. The Zaishu website lists Zaishus for sale for AUD$360, a fortune to an unemployed sign writer or tribal artist in India, so it was easy for them to jump to this conclusion. In reality when you include four return international airfares, hotel accommodation for 1 month, materials, international shipping, laser cutting, varnishing and paying Samparc a lump sum for the artist’s food, accommodation and fees we would be lucky to break even if we sold 50 Zaishus for $400 each. As this project was a speculative experiment I didn’t include my time in the expenses but if the project rolled out into a viable production phase all financial inputs would have to be costed into the final price of the product.

Once the finished artwork was shipped to Australia I kept it in storage for 12 months to get some perspective on the project and so Helen and I could figure out the best context to market and sell the Zaishus in. The India Zaishus, unlike our mass produced ones, were all different and hand painted with various skill levels in all sorts of colours and patterns. While this would be appreciated by someone looking for unique art with a story behind it our retail stores would have a problem with the lack of consistency and the fact that the plywood and textural paint did not look like a brand new product. It would also be best if a customer saw the India Zaishu in the flesh before purchasing which meant sales from our website may be problematic as we didn’t want to deal with returns that take up time and money.

For this reason we opted to launch the Indian Zaishus with an exhibition at a vintage furniture store / art gallery in Brisbane called Day On Earth, owned by artist David Bromley. The opening night was a big success with many people attending but we only sold one Zaishu and that was to cameraman Mike’s mother in law. The gallery also took a 40% cut so the likelihood of returning to India to run another project or to tool up into production stage in India was looking slim.

The problem was that Day on Earth wasn’t the right venue for people to understand the Indian Zaishus as being more than a plywood box painted with Indian patterns. To understand your customer’s demographics, how to market to them and the context of how your product is perceived is as important as the product itself. For the people at the launch who did like the Zaishus it does not necessarily mean they automatically want to purchase one and take it home with them. There are a lot of things that I personally like but for some reason or another do not buy.

Thankfully the Powerhouse Design Museum in Sydney did understand the cross cultural and sustainable theme of this art / design project. They invited us to premier a pilot of the documentary along with myself giving a Q&A hosted by design writer Nell Schofield. Many Zaishus were sold, including to the Powerhouse Museum collection who also used parts of the documentary in a permanent display. The uniqueness of the project was also well received by design journals around the world, presenting the project as a positive model for ethical design that uses sustainability and culture as it’s main program.

It did take a further twelve months to sell all of the 50 India Zaishus which meant that two years after we started the project we managed to break even, not including our time and resources used to perform the sales. This is not a good way to run a business. It could be argued that the positive publicity the project received made up for this but a business can not survive and artists in India or anywhere else can not be paid on merely just good publicity. Accountability and responsibility to give safe, respectful and fairly paid employment to the participating artists and craftspeople should be the main priority. Our project did achieve this but given the product was an AUD$400 non essential art product and retailing is currently at a 20 year low, any plans to roll out production in a second stage would have risked becoming a token PR gesture instead of a financially sustainable industry.

On a personal level, some people may choose to go trekking in Nepal, diving in Thailand or visit museums in Europe to add to their sense of happiness and well being in life. My choice this time was to do the Zaishu India project which has fulfilled similar goals. The project in India has given me wonderful insight into Indian culture and equipped me with the tools and experience to continue working in ethical and culturally relevant design.

As for the artists, one sign writer has opened a coffee shop, the school children are busily studying with the dream to be either an engineer, doctor or business person and tourists commission hand painted Bollywood posters featuring themselves in a fictional Bollywood movie. The world now has 50 colourful Indian Zaishus, hand painted with kindness and happiness in a joint exchange of cultural creativity. We have received emails from delighted Zaishu owners who treasure the cultural richness and originality of their one of a kind Indian Zaishu that often takes pride of place in their homes.

As for the artists, one sign writer has opened a coffee shop, the school children are busily studying with the dream to be either an engineer, doctor or business person and tourists commission hand painted Bollywood posters featuring themselves in a fictional Bollywood movie. The world now has 50 colourful Indian Zaishus, hand painted with kindness and happiness in a joint exchange of cultural creativity. We have received emails from delighted Zaishu owners who treasure the cultural richness and originality of their one of a kind Indian Zaishu that often takes pride of place in their homes.

Matthew Butler founded Zaishu with Helen Punton in 2004. He continues to work as a designer and photographer in Asia.

Wonderful story, working here is India is such a challenge some days but has such rich rewards to offer. I appreciate your comments on marketing, so many good ideas but they need to sell to spread the work around. Thanks for the telling