While there is much to be gained in creative exchange between Australia and India, there is also something to be learnt from each other’s cultural systems. When musicians, dancers, artists and designers from India and Western countries like Australia come together to collaborate, they often encounter a difference in values about the ownership of what’s produced.

While there is much to be gained in creative exchange between Australia and India, there is also something to be learnt from each other’s cultural systems. When musicians, dancers, artists and designers from India and Western countries like Australia come together to collaborate, they often encounter a difference in values about the ownership of what’s produced.

The Western concept of intellectual property is an increasingly formalised system that requires permission for the reproduction of an original work. By contrast, Indian culture seems almost open source. According to Josh Schrei, ‘In Indic thought, there is no trade secret.’ Just as there seem no limits on the way Hinduism can be interpreted, so there seems little to stop anyone using another’s designs or compositions.

The Western system is criticised as skewed to the interests of powerful corporations. This is particularly evident in the epic legal battles over patents between Samsung and Apple, which are seen as a major obstacle to innovation. ‘Patent trolls’ exploit copyright law for profit. And free trade agreements such as the recent one between Australia and USA result in locking up copyright beyond a time when it could be of any possible benefit to creators.

On the other hand, some claim that India is disadvantaged by its informal approach to its culture. While economics such as the USA continue to grow thanks to its stocks of intellectual property, in entertainment and software, India gains little from its cultural exports, such as yoga, music and medicine.

So what happens when an artist from one system travels to the other? Does a Western artist embrace the informality of India, forgoing any ownership of their intellectual property? Should an Indian artist prepare themselves for the cultural jungle of the West by legally registering their cultural assets?

The Brisbane Encounters Festival is a wonderful opportunity to hear from a variety of different cultural voices at the intersection of Australia and India. The roundtable ‘One versus Many’ included perspectives from visual art, music, public art and fashion.

|

|

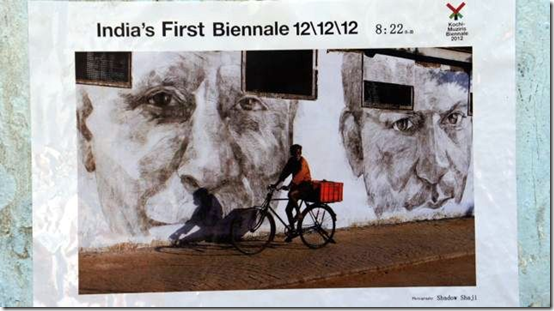

Pat Hoffie is an Australian artist most identified with working collaboratively with communities in Asia, over 35 years. Her initial engagement was with the Philippines, where she had massive canvases painted for the Adelaide Festival. She has since worked in Japan, China, and Vietnam and is now looking to India, where she was a recent participant in the Kochi Biennale.

Hoffie reflected on the title of her early series Fully Exploited Labour¸ which made no pretence to hide the inequity of white artist and Filipino collaborators. ‘Collaboration across cultures is fraught with difficulty: you’re the one who gets the fame and glory.’ While refusing to take a missionary stance towards her subjects, Hoffie does admit some progressive value in collaboration. For the artist, delegating the art production helps take the work beyond the artist’s own frame of reference. However, there needs to be acknowledgement of this contribution.

Aneesh Pradhan is not only a virtuosic tabla player, but also an author on Indian percussion music (see Tabla: A Performer’s Perspective). In his blog, Pradhan protests against attempts by some instrumental players to patent innovations in their instrument. He claims that this ignores the critical role played by expert instrument makers.

Pradhan emphasised that the ownership of Indian classical music was not ‘anything goes.’ Innovation is often located within a family and evolved over generations. Any musician outside that family is expected to acknowledge the musical source, even occasionally tugging their earlobes on mention of the name, as a mark of respect. Acknowledgement is as important as financial benefit from rights management.

For Pradhan, returning to Brisbane brought to mind an earlier incident in 1995, when he had been invited to a recording studio after a music festival. Later, he discovered that what had been proposed as a recording of work in progress, was now ready to be marketed as a CD without any formal agreement between the participating musicians and the record label. Pradhan was deeply anguished that this situation had come about because one of the performers had wanted to appropriate the rights to the recording and that the record label aided him. Eventually, maximum part of the royalties went towards taking care of the large costs for production, which had not been undertaken in the first place with Pradhan’s permission.

Daniel Connell talked about the twin dangers in cross-cultural collaboration of being patronising and romanticising. He advised those interested in collaboration ‘to be ready to be humbled and fooled’. Connell spoke from personal experience, going to India to find a way of being stuck as an ‘angry activist’ working with homeless people in Australia. He ended up staying for a number of years, even finding the usual roles reversed when out of money he found himself exploited by ruthless businessmen. He appreciated how important it was to speak the local language, despite English being widely spoken among the educated classes.

Connell’s experience making public art for the Kochi Biennale confirmed the participatory nature of Indian culture. A number of local street painters had started a poster campaign against the biennale for excluding them. Connell introduced them to the biennale organisers who welcomed them into the program. They were soon painting works on the street. For Connell, the Indian art world is very porous, and contrasts a situation like the Venice Biennale where local artists do not have a place.

Connell is now sharing this experience back in Australia, where he is working with the Sikh community to produce a public art work of a young man who had refused to take off his turban and don a helmet while riding a bike.

Finally, Kay McMahon from Fashion at Queensland University of Technology talked about the changes in the Australian textile manufacturing base, which initially depended on migrants such as Italians and then Vietnamese. Many Australia designers like Easton Pearson are now finding India as the source of valuable production skills. Australia has the advantage of sharing a similar climate with India. The new generation are particularly concerned with the ethical issues of outsourcing. But McMahon cautioned that this ignores the capacity in our indigenous communities. Indian designers themselves were not always able create a global product, as opposed to garments for the local market.

In the discussion, there was a broad consensus that respect should be given to the author of creative goods, even if this wasn’t reinforced by a legal system of copyright. This respect should primarily be an ethical act, expressed principally through acknowledgement of sources. This returns us to the key standard from the first roundtable in Delhi, where it was felt that there should be attribution for any ‘meaningful contribution’ to the work.

But there are now some new questions. To what extent does attribution provide those involved with the necessary capital to sustain their cultural practices? What are meaningful forms of attribution—compare the endless film credits with co-branding on swing tags? Does attribution necessarily imply consent to the use of one’s contribution?

As usual, the roundtable ended with much more to discuss. The encounter of two worlds that emerges from the growing number of creative partnerships between India and Australia continues to generate a lively jugalbandi.