Mala di Jari Kita is an innovative project combining batik with photography by artists Mintio Samantha Tio (Singapore) and Kabul Budi Agung Kuswara (Indonesia) in collaboration by the batik-makers of Kebon Indah, in Indonesia.

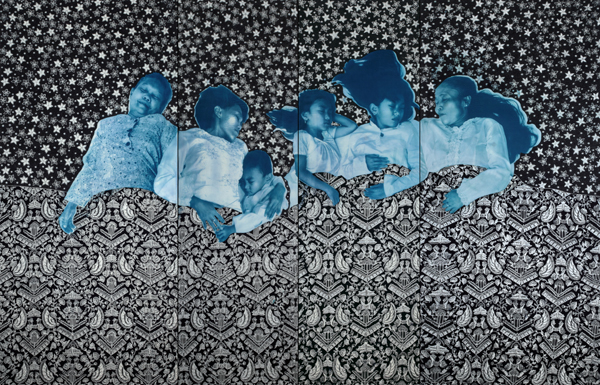

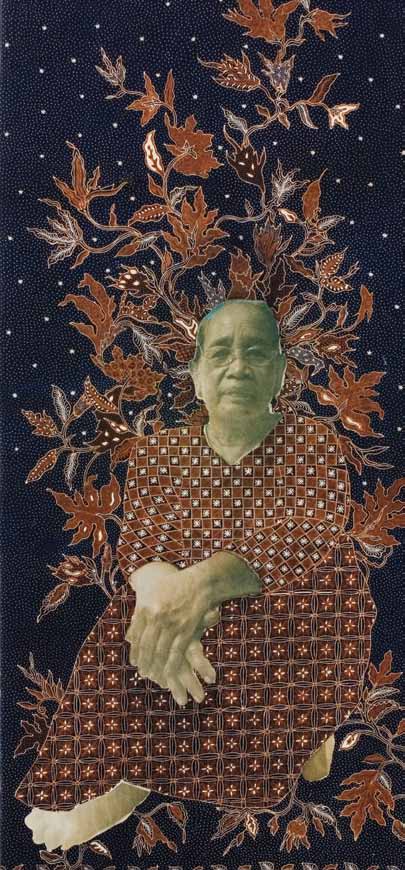

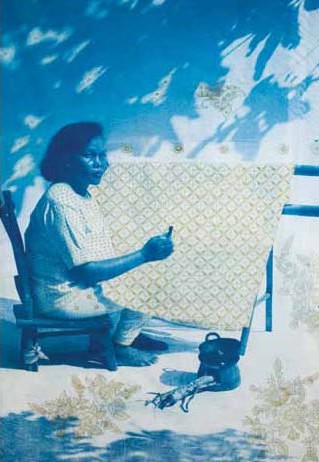

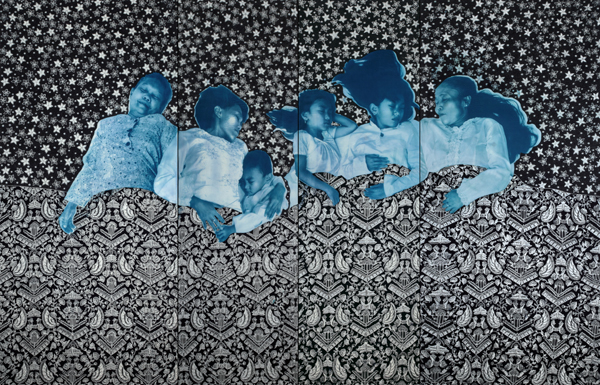

“The Wax on Our Fingers” is a socio-relational visual arts project that celebrates the lives and hands behind batik, a craft that is regarded as Indonesia’s most prided intangible heritage.Artists Mintio & Kabul worked with the batik makers from the Javanese village of Kebon Indah to create unique ‘self-portraits’ combining the realism of photography together with the decorative and symbolic nature of batik motifs. Photographic portraits of the batik-makers are first printed onto batik cloth with the cyanotype technique (sun prints), with their silhouettes penciled onto the fabric.The women then respond to their own image by making batik patterns on them.

“The Wax on Our Fingers” is a socio-relational visual arts project that celebrates the lives and hands behind batik, a craft that is regarded as Indonesia’s most prided intangible heritage.Artists Mintio & Kabul worked with the batik makers from the Javanese village of Kebon Indah to create unique ‘self-portraits’ combining the realism of photography together with the decorative and symbolic nature of batik motifs. Photographic portraits of the batik-makers are first printed onto batik cloth with the cyanotype technique (sun prints), with their silhouettes penciled onto the fabric.The women then respond to their own image by making batik patterns on them.

The amalgam of photography and batik is the outcome of this process and art-making journey with these ladies.The artists, through this project, acknowledge the role of women as culture-makers in the Indonesian society and explore their relationships with their families, the village society and their craft.

The feeling of wax on our fingers

Every time we entered the batik workshop in Kebon Indah, we would greet Bude Sulami with a hearty handshake. The sensation of her fingers always felt warm and sticky from the bees-wax she has been using for batiktulis. ‘Kotor! Kotor!’ she would exclaim with apologies for her wax-coated hands. But in full appreciation of her unyielding commitment to her craft and this journey of ours that she has constantly inspired, the sensation of touching her fingers eternalized as a beautiful one.

Just as with Bude Sulami, every batik-maker we have met in this village has received us with hospitality and patience. We would constantly go back to the workshop of Ibu Suminah and Pak Sukardi for our research, in our drive to create something that no one has done before. In the beginning, we looked to them like curious children at play – messing around with their batik equipment and interrupting their jobs for answers to our questions. Our failures with the techniques and understanding the world that they live in were aplenty. Yet Ibu and Bapak continued to give their time and attention to our practice. Till that day we witnessed the first pieces of the artwork being realized, the joy and pride in making art, feelings that we often experienced in solitude with our previous projects, was magnified and shared by the people that we have worked with.

Just as with Bude Sulami, every batik-maker we have met in this village has received us with hospitality and patience. We would constantly go back to the workshop of Ibu Suminah and Pak Sukardi for our research, in our drive to create something that no one has done before. In the beginning, we looked to them like curious children at play – messing around with their batik equipment and interrupting their jobs for answers to our questions. Our failures with the techniques and understanding the world that they live in were aplenty. Yet Ibu and Bapak continued to give their time and attention to our practice. Till that day we witnessed the first pieces of the artwork being realized, the joy and pride in making art, feelings that we often experienced in solitude with our previous projects, was magnified and shared by the people that we have worked with.

We are artists, not a lone in this world. Everyday we try to think about our role in the society and the impact of our actions. What are the issues we will like to contest and what are the values we hope to protect? Through working with communities, we learn of our tenacity and capacity in art. It is not about establishing the limitations to our work but making our focus clear. We are not social workers or activists, nor do we seek to change anything. The only thing we can do is to make examples of ourselves and question how this change can be made, bringing new perspectives to age old issues. We are artists who create images, sensations, moments and memories that unveil the beauty of everyday people in our everyday lives.

‘The Wax on Our Fingers’ is a project that celebrates the portraits of a small group of people. But with this journey of creation that these people have taken and with their thoughts and emotions, we hope that the work touches anyone who has encountered this work on a universal level. What we have received from the process of creating in this project turned out to be a lot more then what we thought we could give. With the stories we have to share and with this wax we have on our fingers, we hope that the work will touch you in a warm and profound way. —

Yours truly,

Mintio & Kabul Yogyakarta 2012

Centering the marginal: Batik workers in Indonesia by Amalinda Savirani

Bayat area is well known in Central Java as a centre of batik production, specifically the village of Kebon. During the colonial times, the Dutch recognized Bayat to be part of the “vorstenlanden” region together in which the royal capitals of Yogyakarta and Solo are located. The batik motif that batik workers are famous for is the pattern of the “vorstenlanden” areas, which dominated by color of brown (soga) and blue (biron); as well as motifs typical to the palace such as wahyu tumurun. The batik workers from Bayat has long been a backbone of the batik industry in Solo, much to the fact that almost everyone involved in producing batik in Bayat would have either worked at a batik enterprise in Solo or worked from their homes to support the factories there. In short, Bayat is an important place for the batik industry in Java for a long time until today.According to the Klaten statistics of 2010, from total number of 1,598 people in the Kebon Village, 169 women worked as batik makers.

Bayat area is well known in Central Java as a centre of batik production, specifically the village of Kebon. During the colonial times, the Dutch recognized Bayat to be part of the “vorstenlanden” region together in which the royal capitals of Yogyakarta and Solo are located. The batik motif that batik workers are famous for is the pattern of the “vorstenlanden” areas, which dominated by color of brown (soga) and blue (biron); as well as motifs typical to the palace such as wahyu tumurun. The batik workers from Bayat has long been a backbone of the batik industry in Solo, much to the fact that almost everyone involved in producing batik in Bayat would have either worked at a batik enterprise in Solo or worked from their homes to support the factories there. In short, Bayat is an important place for the batik industry in Java for a long time until today.According to the Klaten statistics of 2010, from total number of 1,598 people in the Kebon Village, 169 women worked as batik makers.

Bayat batik workers are known for their fine batik or locally known as “batik tulis”. There are two kinds of batik discerned from the process of making it.The first one batik produced by manual technique, consisting of fine batik (batik tulis) and stamped batik (batik cap). The second is machine-processed batik production, known as printed batik (batik printing). It is labeled as textile with batik motif in order to differentiate between the manual and the machine-based production.The batik discussed in this essay exclusively refers to batik tulis, though it is difficult for audiences without batik knowledge to distinguish between the few techniques.

When the earthquake occurred in Yogyakarta and Central Java in May 2006, Kebon Village was smashed along with its batik industry infrastructure.Thanks to the International Organization from Migration (IOM) and their programs in aide of the earthquake victims, the infrastructure of Klaten was restored and the social and economic activities of the region was revived.Apart from rebuilding the batik production infrastructure, IOM facilitated the marketing of batik products from Klaten by organizing exhibitions and various events in Yogyakarta.The current situation of the batik workers in Kebon can hardly be separated from the efforts of these programs.

This stable environment of batik production in Kebon should also be situated in the macro-context of the batik economy in Indonesia. It was in early year 2000 when Edo Hutabarat, a designer based in Jakarta, made two revolutionary statements in the way batik was worn.The first was from his experiment with making batik on cotton fabric. Previously, this technique was commonly done on silk. It demanded a high price for each piece of batik, establishing it as a luxury item that is expensive and unreachable for ordinary Indonesians. Demand for such batik was low. Only the rich and batik collectors from abroad could afford it. But due to Hutabarat’s innovation with cotton, fabric made out of batik tulis became affordable. Hutabarat also modernized batik by creating casual designs, making the fabric appropriate for informal events and more popular with the younge. Once used to be associated with formal events and the older generations, batik appreciation under the influence of Hutabarat was extended across generations and beyond the formal events.These breakthroughs resulted in the demand for batik tulis and textiles with batik motifs to increase till today.

Alongside this high market demand for batik products was also the decentralization of power in Indonesian politics in 2001. The impact of this change facilitated the local governments in strengthening their authority to decide for the economic betterment of their regions.This included the set up of batik production centers which sprung up all over the archipelago. The result of these initiatives paved the way for a variety of interests in batik. Findings and recognition of batik motifs unique to Papua, an eastern province of Indonesia, start to get acknowledge by the public. In Solo, a batik carnival by the local government of Surakarta is annually held, as part of tourism strategy and to popularize batik local to the city.All of these events reached a climax in October 2009 when the UNESCO inaugurated Indonesian batik as an intangible cultural heritage of the world.

Marginal Batik workers

Despite the new excitement of the batik economy in Indonesia over the past ten years and its economic impact, little is known on how intricate the batik making process is and the fate of batik workers.The workers behind the production of batik, mainly female, are barely mentioned.The batik discourse in Indonesia has been focusing too much on the artistic and economic dimension, neglecting the “people aspect” which has all along been the most important in batik production.Whilst in reality, the fate of Indonesian batik for the future lies in their hands.

Amidst all the discussions on batik, there has been hardly any talk on the generation crisis among the batik workers and the absence of a wage standard. Not to mention the complicated and uneven relations between the batik workers with the owner of the batik production house, middlemen, sales outlet owners and finally the last chains of batik distribution in big cities such as Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta. Batik workers, constituted mainly by women from the village, have always been at the lowest ranks of the production cycle.They are paid at maximum IDR 12,000 (USD 1.3) per day, or sometimes they are paid at once a total amount that is more or less to the same amount as a per-day payment. Due to this unfortunate situation, it is not surprising how the younger generations take no interest in becoming a batik maker.

Filling the gap

In context of the marginal position of batik workers, the collaboration project of Mintio and Kabul with the batik makers of Kebon village, speak of something that has been missing in the context of the batik Industry in Indonesia

– namely to exert the existence of these people. In this collaboration, the end product consists of the typical batik motifs to Bayat (namely wahyu tumurun, buron worno, daun telo), placed side by side the very women who crafted the batik fabric. Usually, it is the motifs that people pay attention to when they observe a piece of batik.This collaboration is beyond my imagination. For more than two centuries of batik history in Indonesia, I have never though that these batik workers can be revealed in their final products. If there were to be somebody to be displayed in association with a piece of batik, it would be the owner of batik production chains or perhaps the collectors, never the workers.Thus, for me, this collaboration leads to kind of statement that Mintio and Kabul has made in advocacy for the status of batik workers.

Mintio and Kabul did not hit the streets to hold a demonstration on the marginalized fates of the batik makers. Instead they played with and innovated the techniques of batik tulis by combining it with the photography technique of cyanotype. This collaboration has several radical dimensions in the conventions of traditional batik. The first is in a kind of rebellion towards motifs that are considered sacred. As such motifs are final and cannot be replaced or disassembled with the input of other elements, the way in which the artwork appropriated the batik motifs is out of the ordinary. The second is in placing the face of a batik maker directly into the fabric and batik motifs, positioning it as the primary focus on the fabric whilst subjugating the motif as a decorative backdrop. The usual case is for the motif (other than the color) to be at the centre of attention. But in this collaboration, it is the portrait of the batik maker that is placed in priority to the composition, when usually their image does not bear a single trace on the fabric. Further more, this work is a clear statement to me on the existence of batik today. In picturing the photos of the batik women with their children and the cross-generational relationships of the batik makers onto fabric, Mintio and Kabul has created a space for the batik makers to appear and exist in the batik discourse. For the batik makers to present their work as something of their own identity is a situation that may never happen in their imaginations throughout their entire lives in their craft.

On a piece of cloth by Antariksa and Titarubi

An inseparable part in the internationalization of art today is the concentration of art infrastructures and activities in urban areas. Internationalization has standardized the concentration of fine art’s infrastructures (galleries, museums, schools, auction houses, etc.) in urban areas. It also has standardized how the infrastructures work (how an exhibition and auction should be held; how an artwork should be created; how a criticism should be written, etc.), and how artworks should be consumed — which ones are good or not, which ones are worth buying and collecting, etc. It can be said that the history of art today is being compiled and runs as the history of urban areas and communities.

Then how can we comprehend the project titled “The Wax on Our Fingers” initiated by Samantha Tio (Mintio) and Budi Agung Kuswara (Kabul) — an art project that engaged itself with a rural community of batik makers?

Batik and village sound like an exotic idea, one that represents something ancient, something from the past.And the attention to batik and rural areas usually works as a romantic imagination about a search for something that is (or was) left behind, gone, missing, which later turned into philanthropic ideas — to preserve, assist, or promote something those abandoned and missing things — or into revolutionary ideas and social designs that can empower and transform a community.

In this art project, Mintio and Kabul in fact tried to abstain themselves from such a philanthropic and revolutionary spirit. That kind of spirit, to them, seems to intentionally place the artists in a higher position than other members of a community.They argued that the real advances and changes of a community are beyond art’s task. Changes in a community are only possible if the community itself wants to change, and the task of art is to offer possibilities and different points of view regarding those changes.

The creative strategy that they chose is a participatory strategy, namely building a relationship as long and deeply as possible with community members, with whom they work together. This kind of strategy comes with compromises and exchanges of experiences and knowledge. Mintio and Kabul came up with the idea for this project, bringing their entire experiences and knowledge about the world of fine art — about photography, about printing techniques, about ways to sell artworks, about connections, etc. But instead of accepting those things submissively, members of the batik making community weighed those ideas, questioned them, transformed them, modified them to make them correspond with certain situations, tastes, and needs, as well as giving Mintio and Kabul the experience and knowledge about the techniques and the working system of making batik, as well as teaching them about the culture of a rural community.

There are two prominent media in these works, namely the cyanotype and the batik techniques. Both come from the same principle: rintang warna (color blocking). It is a way of overlapping colors on parts that are meant to be covered. In it lie fundamental differences of both techniques.

In batik, the first thing that has to be covered by colors is the basic shapes, and then the covering and peeling processes are done repeatedly, up to 20-30 times, until the basic shapes and the rest of the background colors meet with the expected result. In cyanotype, however, it only needs one time of color application process to give the basic shapes their colors.The color in cyanotype is not applied per se — it is a chemical process that reacts to light, just like in the process of printing an image in photography.

Of a long process of experiment, Mintio and Kabul decided to make use of the cyanotype printing process — which was found by Sir John Herschel in 1842, that relies on iron salt’s sensitivity to light. In this process, a piece of cloth is brushed with iron salt solution and left to dry in the dark.The objects reproduced will be in the form of a negative image, which will then be dried under direct sunlight.The light of a UV lamp can also be used for smaller images.After about 15 minutes, a white impression of objects will be formed on a blue background.The printed material is then washed, resulting in an oxidation that gives the color cyan, hence the term blueprint.

Different techniques require different tools. Batik is known as a traditional technique, in which colors are applied manually — especially in hand drawn batik — using liquefied wax. However, the cyanotype method of color application requires a special mechanism in the form of a device that can print on transparency film, thus a technology more sophisticated and intricate than the one involved in batik’s color application is needed. For batik, the intricacy lies in the process, no matter how simple the technology is: the pouring of liquefied wax; the dyeing process; and the boiling that leads to the peeling off of the wax, all are done repeatedly, depending on the expected color result.

The challenge of the cyanotype kind also lies on the scarce materials:Ammonium iron (III) citrate and potassium ferricyanide, which can only be obtained in Jakarta.The batik’s materials, on the other hand, can be found in batik production areas considering they are needed on a daily basis.The materials for the batik can give richer colors than the cyanotype, which produces a certain range of blue only.

From these distinctions, we can deduce how the artists involved are different in terms of knowledge and background. Kabul and Mintio are both art school graduates, born in the 80s, hailing from two different countries: Indonesia and Singapore.Yet they worked together with a community of batik makers in Kebon Indah Village, Klaten.

Cyanotype and batik on cotton.This is how Mintio and Kabul collaborates. It seems to whisper to us about the encounter of a technique that is more recent and a technique that has stood the test of time, one that has been the practice of batik making communities from generation to generation.

Each technique brings its own information: it is apparent that there is effort in incorporating West and East; new technology and old technology; an individually discovered technique and a mass knowledge. Speed, as it happened, also played a role: the cyanotype creates shapes that can be seen in just 1-2 days, while the batik takes 1-3 months.

The encounter and incorporation result in different interpretations, depending on the perspectives. One may see a piece of batik, or a photograph, or the combination of both.The quick and the slow techniques are combined. Both are in one piece together. It gave not only new experiences to the artists involved.As much as a piece of batik is never acknowledged as a work of just one individual, these pieces carry the names of the artists.And they are introducing us to new identities.

THE CREATIVE INTERACTION between Mintio and Kabul and the batik makers of Kebon Indah is interesting because the pieces created out of this project had not been fully controlled and predicted by those involved. Here we can see how interactions between individuals, between cultures, between the different processes of creating works of art, and between the artworks themselves, become equally important.

What they did is not a standard formula in answering aesthetic or identity problems in fine art. It is also not a panacea that answers all the dynamics between the urban and the rural. Through this project, they are offering a bold, creative way in dealing with complicated, challenging problems.

This text is taken from the catalogue of their exhibition in Indonesia. It is on display at Baba House Singapore until end of January 2015.