Minna Loft, a graduate from jewellery at Monash University, reflects on her recent experience learning about Indian crafts in northern India

India never ceases to amaze me, continually impressive and unpredictable. The generosity that I have experienced in India is breathtaking. I recently headed back there for my own research and intrigue. With previous experience of Indian life, I have travelled to many parts of the country. Motivated by my love of textiles and a sense of compassion for the artisans that create such wonders, I set out to investigate the many facets of the creative communities in India.

India never ceases to amaze me, continually impressive and unpredictable. The generosity that I have experienced in India is breathtaking. I recently headed back there for my own research and intrigue. With previous experience of Indian life, I have travelled to many parts of the country. Motivated by my love of textiles and a sense of compassion for the artisans that create such wonders, I set out to investigate the many facets of the creative communities in India.

As I wandered and rode through towns of the North-Western states, I observed many looms left desolate. It was ironic to see many shops in the main town filled with coloured, woven shawls. In an attempt to see the working environments and meet the people responsible for such wonderfully vivid creations, I approached numerous shop assistants and tourist information centres with an expression of interest. No one could tell me exactly where these artisans hid, highlighting to me the disengagement of artisans from the public view. Unaware of the working and paying conditions of such artisans I persistently searched for a shop with ethical merit. Finally, on my last day in this region, I discovered Hyund, a small shop that stocked woven products made by a group of women working from their home environments. I was consistently confronted with a lack of ethics in the distribution of craft and an absence of recognition and engagement for the artisans.

It was in Delhi, through my dear friend Divya Singh, that I was exposed to the true beauty of another type of traditional Indian craft: Chikankari embroidery. Chikankari is a prime example of the way in which craft has developed and evolved throughout history. Originally made specifically for the wealthy monarch of Lucknow, Chikankari was intricately executed with very fine, white thread. The fragility and refined detail of Chikankari was an essential indication of value, with quality informing price. Due to the downfall of the monarch, the condition and prestige of Chikankari has gradually been lost, causing the quality to suffer immensely. Chikan artisans are now amongst the poorest in their community. To experience an attempt to revive this craft, I was introduced to the delightful Mita Das.

It was in Delhi, through my dear friend Divya Singh, that I was exposed to the true beauty of another type of traditional Indian craft: Chikankari embroidery. Chikankari is a prime example of the way in which craft has developed and evolved throughout history. Originally made specifically for the wealthy monarch of Lucknow, Chikankari was intricately executed with very fine, white thread. The fragility and refined detail of Chikankari was an essential indication of value, with quality informing price. Due to the downfall of the monarch, the condition and prestige of Chikankari has gradually been lost, causing the quality to suffer immensely. Chikan artisans are now amongst the poorest in their community. To experience an attempt to revive this craft, I was introduced to the delightful Mita Das.

Seeing Lucknow through the eyes of Mita was a real pleasure and joy. As we wondered through the historic streets of Lucknow, I began to see the complexities and challenges Mita has faced in the pursuit of maintaining the integrity and value of Chikankari and its artisans. She has developed an organisation that allows a more realistic livelihood for the many women who have been born into this trade. Realising the economic realities, Mita has created a platform for Chikan embroiderers to improve the condition of this craft, as well as become economically stable. Involving a significant number of people in the design process, Mita encourages traditions to continue and develop.

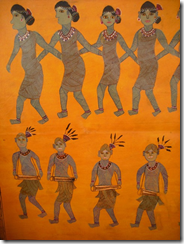

The Museum of Tribal Arts in Bhubeneswar was a platform for artisans to present their craft skills on a commercial and informative level. Most Indians would not even know that it exists and I was lucky to stumble across it. A ten day project was held involving a selection of artisans from fourteen different states of India, to exhibit and sell their wares at an open air craft fair. I sat with beautiful tribal girls who had small knives in their hair. These knives were used as a defence in the jungle, as well as a tool to cut berries and embroidery threads. I watched as women beaded necklaces made with two needles. There were women with back strap looms and men painting. There were people making baskets and twining string from grass. There is an intrinsic value and beauty that comes with the hand-made objects, but also a necessity to communicate and share it. To understand how far reaching the language of craft is.

The Museum of Tribal Arts in Bhubeneswar was a platform for artisans to present their craft skills on a commercial and informative level. Most Indians would not even know that it exists and I was lucky to stumble across it. A ten day project was held involving a selection of artisans from fourteen different states of India, to exhibit and sell their wares at an open air craft fair. I sat with beautiful tribal girls who had small knives in their hair. These knives were used as a defence in the jungle, as well as a tool to cut berries and embroidery threads. I watched as women beaded necklaces made with two needles. There were women with back strap looms and men painting. There were people making baskets and twining string from grass. There is an intrinsic value and beauty that comes with the hand-made objects, but also a necessity to communicate and share it. To understand how far reaching the language of craft is.

Often in India, craft techniques are passed down from generation to generation, this being the prime education of many peoples lives. Yet, how do they begin to recognise their rights and financial worth? How do they understand that what they are doing is valued in another part of the world?

Through the commercialisation of a product, the artisan has the opportunity to gain economic stability. Yet to maintain the value of old traditions, it is necessary to give credit to the artists for their creative work. This is not always the case. I witnessed the way in which artisans have been given access to a range of opportunities and the different ways in which their skill is valued or sometimes devalued within society.

Traders are responsible for the progression of craft and culture in a wholesome and ethical manner. Through being exposed to such outcomes, I recognise the value and luxury of having access to such a privileged education. I feel the responsibility to allow these skilled artisans to have the same access and opportunities as I do.